Principle of Charity

The Principle of Charity demands that one interprets a speaker's statement(s) in the most rational way possible. In other words, when ascribing to this principle, you must consider the strongest possible interpretation of your fellow interlocutor's argument before subjecting it to evaluation. The overarching goal of this methodological principle is to avoid attributing logical fallacies, irrationality, or falsehoods to the statement of others when a rational interpretation of that particular statement exists. Put simply, your default position walking into an argument is that the other person is intelligent, which will help constrain you to maximize the truth or rationality in their argument.

When an issue is encountered with an argument, you should assume that this error is unintentional as long as it is reasonable to do so. Whenever possible, you should attribute these errors to a misunderstanding on their part instead of intentional chicanery. Hence, when engaging in a discourse, embracing the Principle of Charity requires embracing Hanlon's razor as well:

“Never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by incompetence.”

A Successful & Critical Commentary

Philosopher Daniel Dennett, from his book “Intuition Pumps and Other Tools for Thinking,” lists the following four steps to implementing the Principle of Charity whenever engaging in a discourse.

You should attempt to re-express your target's position so clearly, vividly, and fairly that your target says, “Thanks, I wish I'd thought of putting it that way.”

You should list any points of agreement (especially if they are not matters of general or widespread agreement).

You should mention anything you have learned from your target.

Only then are you permitted to say so much as a word of rebuttal or criticism.

By following these steps, you are now confronting the best possible version of the argument, which is called a steel man argument. Thus, by following the Principle of Charity, you will eventually reach the steel man argument and, from there, your discourse can continue. Note, this is the opposite of the straw man fallacy where you deliberately adulterate the argument to make it easier to attack.

In practice, how you choose to implement the Principle of Charity is completely up to you. Moreover, the amount of charity you wish to give your fellow interlocutor is also up to you. You may do as little as only correcting glaring issues while allowing smaller faults to pass through. Or, you may choose to completely overhaul their argument where you would essentially be replacing their entire argument with a new and improved version. If this is the case, be aware that the owner of the argument must be open to the replacement; if they're not, then you have made no progress. Regardless of how charitable you choose to be, by improving the argument, you have moved the discourse closer to truth.

Examples

1)

Humans are capable of achieving momentous feats when they choose to work collectively. We have put a man on the moon, harnessed the energy of the atom, have formulated theories to completely describe our reality from the quanta all the way up to galactic scales.

Therefore, we should be able to figure out how to harness the power of nuclear fusion; the energy of the stars.

Uncharitable Explanation: The premise that we have formulated theories to completely describe our reality is false. We currently don't possess a theory of everything, which, if we're being pedantic, is how this statement must be interpreted due to the word completely. Thus, since the argument possesses a false premise, it can be neither sound or cogent; therefore, it's a bad argument and should be rejected.

Charitable Explanation: Most people are already aware that humanity has yet to craft a theory of everything. The chances are very good that our fellow interlocutor does as well and simply made a minor mistake in wording. Therefore, instead of interpreting the argument as if there's a false premise, we interpret it charitably and assume that he/she simply made a mistake and was not referencing a theory of everything.

The new, charitable argument takes the following form:

Humans are capable of achieving momentous feats when they choose to work collectively. We have put a man on the moon, harnessed the energy of the atom, have formulated theories to describe our reality from the quanta all the way up to galactic scales.

Therefore, we should be able to figure out how to harness the power of nuclear fusion; the energy of the stars.

Note, the argument is essentially the same as before, except that we have charitably eliminated the word completely from it.

2)

Patrick eats meats frequently and, thus, doesn't care about the environment.

In this case, there is a suppressed premise (i.e., an assumption that is left out of the argument), which is linking Patrick eating meat regularly and him not caring about the environment. So, how should we interpret this suppressed premise? In practice, you should:

Gather any available evidence from the other person's argument including clues from stated premise(s), conclusion, body language, etc. that you can use to guide your decision.

Apply the Principle of Charity.

When you are faced with an argument that has missing parts, such as a suppressed premise, you should reconstruct it as charitably as possible making sure to avoid adding premises that are obviously false. Moreover, you should add the most plausible premise that will help to logically connect the premises to the conclusion.

The original argument could have the following suppressed premise added:

Patrick eats meat regularly.

[People who engage in eating meat frequently don't care about the environment.]

Therefore, Patrick doesn't care about the environment.

Uncharitable Explanation: With this particular added premise the argument is clearly valid, but is unsound as the added premise is false. That is, there is no evidence that all people who engage in the frequent consumption of meat products don't care about the environment. It is entirely possible an individual who engages in frequent meat eating still cares very much for the environment. The individual may need to have a higher percentage of their diet consist of animal products due to dietary restrictions as a result of severe allergies, but is obsessive about recycling, gives free public lectures on the impacts of Global Warming, etc.

Since we have added a false premise to the argument, we are not doing a very good job of following the Principle of Charity here. A more charitable interpretation of the argument is:

Patrick eats meat regularly.

[Many people who engage in eating meat regularly don't care about the environment.]

Therefore, Patrick probably doesn't care about the environment.

Charitable Explanation: The more notable change to the argument is that the added premise shifts the argument from deductive to inductive through the addition of the words many and probably. While there isn't much information available to determine whether the argument is intended to be deductive or inductive, the more charitable interpretation is to portray the argument as inductive. Moreover, drawing from experience, the argument type most often encountered in everyday discourses will be inductive, which further supports the decision to recast the argument in inductive form.

Furthermore, treating the argument as inductive allows us to move away from using an absolute. In other words, instead of talking about all people, we are now talking about many people. This small change makes it explicit that we know some people who eat meat regularly and, nonetheless, still care deeply for the environment. Moreover, this suppressed premise stands a better chance of being strong - we are now using terminology associated with inductive arguments - than our previous false premise, which signals to us that we are indeed being charitable here.

3)

While the number of people falsely claiming sexual assault is quite low (2-10%) [1], there are still many examples where the victim (predominantly women [2]) is not trusted when he/she does come forward. Even more disturbingly, sometimes these sexual assault victims become the target of harassment themselves from supporters of the accused. Do you really think it's safe to come out and tell your story if you have been assaulted?

What exactly is the conclusion here? As you can see, it has been suppressed and a rhetorical question has taken its place. Now, we need to rewrite this argument in standard form where we have to create a conclusion. As always, there are a number of options that we could choose, but let's begin with the following:

While the number of people falsely claiming sexual assault is quite low (2-10%), there are still many examples where the victim (predominantly women) is labeled a liar when he/she does come forward. Even more disturbingly, sometimes these sexual assault victims become the target of harassment themselves from supporters of the accused.

Therefore, it's unsafe for all victims of sexual assault to come forward.

Uncharitable Explanation: The argument now has a proper conclusion, but there's an issue with its structure. It is clearly deductive due to the inclusion of all, but the conclusion doesn't necessarily follow from the premises, which renders it invalid and, thus, a bad argument. Expatiating, while the premises are both true, they don't support the conclusion that it's unsafe for all victims to come forward. Although it may be rare, there are cases where victims who come forward are both believed and not harassed. Hence, we have not been charitable with this conclusion as the argument is rendered bad.

Let's try again; this time being a bit more charitable.

While the number of people falsely claiming sexual assault is quite low (2-10%), there are still many examples where the victim (predominantly women) is labeled a liar when he/she does come forward. Even more disturbingly, sometimes these sexual assault victims become the target of harassment themselves from supporters of the accused.

Therefore, it's probably unsafe for victims of sexual assault to come forward.

Charitable Explanation: Here, as we've done before, we shifted the argument from deductive to inductive by adding the word probably and removing the word all. Moreover, the conclusion still aligns with the overall message of the original argument while giving it a better chance of being good. Note, the argument may still be bad, that's up to you to decide, but we have been charitable and done our job as critical thinkers by giving the argument the best chances possible of being good.

Notice how we shifted the argument from deductive to inductive for the last two examples. In general, this is a good rule of thumb to follow for the Principle of Charity unless the intentions of the argument clearly points towards deduction. In practice, most individuals you encounter will not know the difference between the two as they lack the training (be sure to point them to this site!). That said, you are being charitable and giving them a better chance at a good argument if you treat them as inductive. Your fellow interlocutor may not be able to definitively prove their claims, but they may provide very strong support. You'll have to work harder in the end to show their argument is bad, but you'll be better for it.

R.E.S.P.E.C.T.

There's a limit to the Principle of Charity. Ultimately, the goal is to give the other person a fighting chance of presenting a good argument for you to either rebut or accept. However, any changes made to the argument should be within reason. Just as you don't want to reformulate the argument so that it's bad, you don't want to unnecessarily inject hyperbole and distort the argument to a degree where it barely represents the initial argument presented, but still remains good. Further, whether or not you wish to reach the steel man argument (i.e., the best possible version of the argument) is completely up to you, but it’s usually the optimal strategy for everyone involved if truth, not deception, is the goal.

What is more, there are a number of reasons to be charitable. For example, if you believe the conclusion of the argument, you'll want the steal man argument in order to protect that position against dissenting views. On the other hand, if you don't agree with the conclusion, you will be better off if you confront the steal man argument so that there's no further disagreement. If there is disagreement over a conclusion and the strongest version isn't addressed, the owner of the initial argument could claim that the argument is not what he/she really meant anyway. At the least, this will set you back as you will then have to agree upon a new argument followed by another discourse. At the worse, this could be the end of your discourse and both of you will walk away having not made any progress.

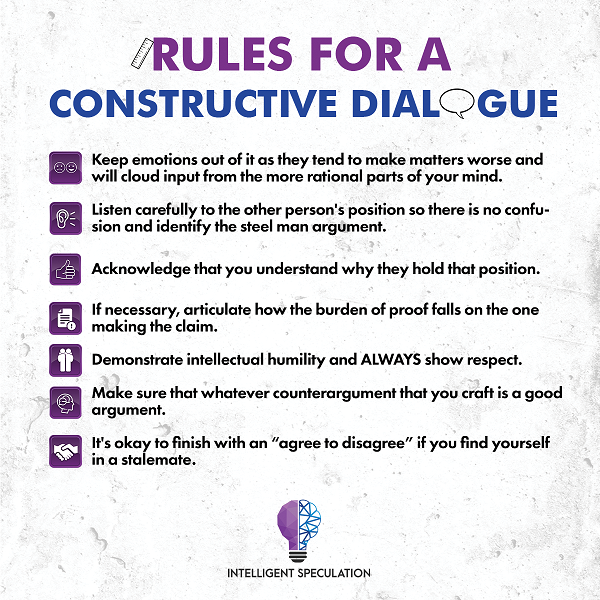

All that said, as the Principle of Charity is only one aspect of a constructive dialogue, what exactly is the best way to try and convince people of the error(s) in their argument? Here are a few thoughts:

These are some strategies I implement personally when engaging in a discourse with others. However, not everyone that you encounter in life is going to be reasonable and these tactics may not work to help them realize the errors in their thinking. Nonetheless, this doesn't mean your attempt is futile. Whether or not you are successful in changing their minds, the exercise will have forced you to objectively analyze your own worldview as well as refined your skills in logic.

Conclusion

In the end, by following the Principle of Charity, if you can walk away from a discourse with the steel man argument for your position or if you were able to show that the steel man argument for your fellow interlocutor’s argument is false, you've made progress. This is what critical thinking is all about. You are ultimately a participant in a verbal waltz where you and your partner are tasked with moving yourselves closer to truth. While not all participants may ascribe to the critical thinking philosophy, you do, and accordingly, must lead this dance by example.

References

[1] Kay, Katty. The truth about false assault accusations by women. BBC World News (2018).