Scientific Consensus

The term “consensus” is often encountered in daily life on the news, in casual conversation, on social media, etc. and most would interpret this word as the majority of opinion. However, once you attach the word “scientific” in front of it, you move beyond the colloquial terminology into a definition which carries far more weight, but is yet often misunderstood.

Criterion for a Consensus

The scientific consensus has a very precise, philosophical definition that is far more formal than its cousin encountered in common vernacular. However, before we get to the criterion for a scientific consensus, it is important to note that it is entirely predicated on evidence. A scientific consensus is not an opinion, survey, popularity contest, etc. among scientists. It is entirely dictated by the quality and quantity of evidence published in peer-reviewed journals. Further, the consensus is not absolute. In other words, being that scientists are an intellectually humble crowd, we are always open to the possibility that new evidence could potentially overturn the current consensus.

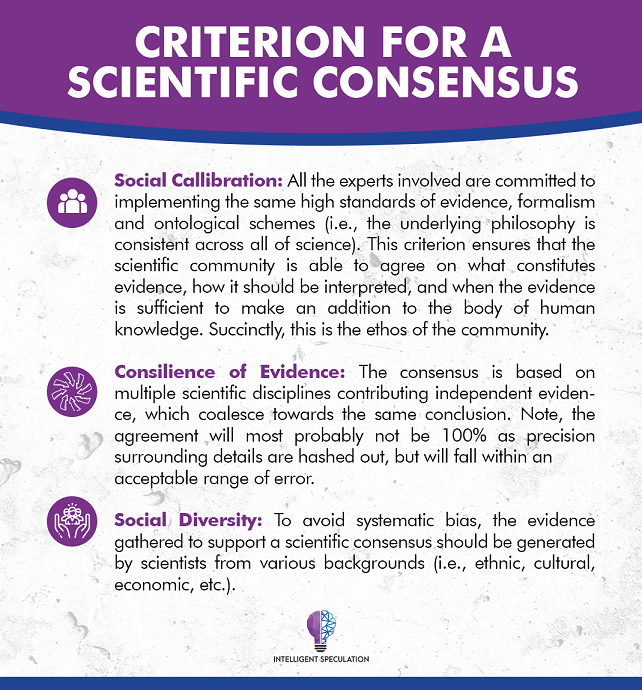

The three criterion for an evidence-based consensus are [1,2]:

To recapitulate, the scientific consensus is an inevitable consequence of scientists operating within a strict system that demands a standard of excellence coupled with evidence gathered across the breadth of the sciences. I say “inevitable” because if we embrace the philosophy (i.e., empiricism) that there are scientific facts about the world around us, then they should be capable of discovery through the application of the scientific method. Moreover, given enough time and routine application of the scientific method across varying domains of expertise, the confluence of all the evidence should then point to this scientific fact. This convergence upon a scientific fact is the scientific consensus.

Metaphorically, if you were to view the scientific method as a machine that is responsible for filtering information about the world to distill scientific fact, then scientists are the individuals who both program the machine and facilitate its operation. Once the program is written (i.e., the axioms for operation), then the scientist merely operates the machinery and doesn't choose what comes out the other end. Therefore, after a period of time, if many scientists from around the globe operate this machinery and these machines keep producing the same finished product, the collective observation that these machines produce the same product every time is analogous to the scientific consensus. Quintessentially, the scientist is a highly trained member of society who, following a strict method refined through many years of rigorous training, acts as a conduit through which scientific facts about our world flow.

Definition of Fact, Law, and Theory in Science

Before articulating the difference between a scientific consensus and a scientific theory, it is important to understand the definitions of fact, law, and theory within science as they are often misconstrued.

Scientific Fact: An observation that has been repeatedly confirmed and is accepted as “true.” However, within science, truth is never final and what is accepted as fact today could be modified or even discarded tomorrow.

Law: A descriptive generalization about how some aspect of the natural world behaves under stated circumstances as demonstrable by a mathematical equation.

Theory: An explanation about some aspect of the natural world that has a broad and deep body of evidence to support its acceptance. It can incorporate facts, laws, inferences, and tested hypotheses.

Note, the word “fact” within science is different than the everyday use of the word “fact.” This is why I have chosen to use the term “scientific fact.” Within everyday parlance and even within philosophy, the word “fact” is used to refer to something that is immutable (e.g., the Earth is the third planet from the sun or that George Washington was the first President of the United States) [4]. However, within science, as explained above, a “scientific fact” or “truth” is malleable and subject to change if the evidence demands it.

Since “theory” is another word, similar to “fact” and “consensus,” that is often misunderstood as the definition in common vernacular is different than that used in science, let's look at a few formal definitions for further clarification.

The United States National Academy of the Sciences defines scientific theories as follows [5]:

“The formal scientific definition of theory is quite different from the everyday meaning of the word. It refers to a comprehensive explanation of some aspect of nature that is supported by a vast body of evidence. Many scientific theories are so well established that no new evidence is likely to alter them substantially. For example, no new evidence will demonstrate that the Earth does not orbit around the sun (heliocentric theory), or that living things are not made of cells (cell theory), that matter is not composed of atoms, or that the surface of the Earth is not divided into solid plates that have moved over geological timescales (the theory of plate tectonics)...One of the most useful properties of scientific theories is that they can be used to make predictions about natural events or phenomena that have not yet been observed.”

From the American Association for the Advancement of Science [6]:

“A scientific theory is a well-substantiated explanation of some aspect of the natural world, based on a body of facts that have been repeatedly confirmed through observation and experiment. Such fact-supported theories are not "guesses" but reliable accounts of the real world. The theory of biological evolution is more than "just a theory". It is as factual an explanation of the universe as the atomic theory of matter or the germ theory of disease. Our understanding of gravity is still a work in progress. But the phenomenon of gravity, like evolution, is an accepted fact.”

How is a Scientific Consensus different than a Scientific Theory?

Essentially, the scientific consensus is a statement about the integrity of the evidence. That is, the volumes of evidence are robust enough to place the utmost confidence in the conclusion(s) reached. Just as with a theory, a consensus can be augmented or even rejected as more evidence is gathered. However, once you have arrived at either, it is highly unlikely given the depth and breadth of evidence in support that it will be drastically changed or overturned. Further, a consensus usually revolves around one hypothesis (e.g., humans are causing the Earth to warm, GMOs are safe for human consumption, etc.) whereas a theory can incorporate multiple hypotheses as it generally encompasses a larger, overarching framework describing an aspect of the natural world (e.g., the general theory of relativity to describe gravity). Hence, a scientific consensus is not a scientific theory, but a scientific theory is usually supported by a scientific consensus.

Examples

1) There are a few examples of where an independent scientific organization will release a statement publicly on the state of the scientific consensus for a given issue. In this instance, the American Association for the Advancement of Sciences (AAAS) - an international non-profit organization that seeks to “advance science, engineering, and innovation throughout the world for the benefit of all people”[6] – has this to say about anthropogenic (i.e., human-caused) climate change/global warming [7]:

“The scientific evidence is clear: global climate change caused by human activities is occurring now, and it is a growing threat to society. Accumulating data from across the globe reveal a wide array of effects: rapidly melting glaciers, destabilization of major ice sheets, increases in extreme weather, rising sea level, shifts in species ranges, and more. The pace of change and the evidence of harm have increased markedly over the last five years. The time to control greenhouse gas emissions is now.”

2) AAAS also has this to say about the scientific consensus surrounding genetically modified foods and safety [8]:

“The science is quite clear: crop improvement by the modern molecular techniques of biotechnology is safe. The World Health Organization, the American Medical Association, the U.S. Health Organization, the British Royal Society, and every other respected organization that has examined the evidence has come to the same conclusion: consuming foods containing ingredients derived from GM crops is no riskier than consuming the same foods containing ingredients from crop plants modified by conventional plant improvement techniques.”

3) Similarly, the National Academy of Sciences, another prestigious scientific organization, has released the following statement surrounding the scientific consensus on vaccine safety [9]:

“Vaccines offer the promise of protection against a variety of infectious diseases. Despite much media attention and strong opinions from many quarters, vaccines remain one of the greatest tools in the public health arsenal. Certainly, some vaccines result in adverse effects that must be acknowledged. But the latest evidence shows that few adverse effects are caused by the vaccines reviewed in this report.”

Note, if you are an intellectually humble individual as all Critical Thinkers are, you don't get to pick and choose which scientific consensus to believe in. As discussed in The Scientific Method article, science isn't a belief system, it's a process. Therefore, the result(s) of that process, if the method is strictly adhered to, aren't subject to our beliefs as they just are. In other words, the results are scientific fact.

Personally, I used to be a buffet-style science enthusiast as I was skeptical of the consensus surrounding both vaccine and GMO safety, while remaining a staunch proponent of the consensus surrounding anthropogenic global warming. Candidly, I was falling victim to the Dunning-Krueger Effect as I didn't possess enough information to craft an adequately informed position on the matters, which lead me to arrogantly believe that I was somehow more informed than the rest of the scientific community on these issues. In short, I was wrong and didn't realize how wrong I was. Luckily, as a lifelong learner, I discovered the tools of critical thinking (i.e., logic, cognitive biases, intellectual humility, etc.) and have since learned the errors of my ways and reformed my positions to align with the evidence.

Why Does it Matter?

The scientific consensus represents some of the most reliable knowledge available to us on a given topic. It is an invaluable product of the scientific method that can help guide us towards optimal, evidence-based decisions, which are the best decisions available. That said, as was discussed in Scientific Argumentation, science is a self-correcting process and the scientific consensus is certainly not immune to this foible. However, this certainly doesn't mean that we should now reject it in favor of an alternative, less reliable epistemological framework (i.e., a framework of knowledge) as we would then be falling prey to the Nirvana Fallacy. Again, while imperfect, it is nevertheless the best available option that we currently have when it comes to knowledge credibility.

Conclusion

The Scientific Consensus is one of the strongest possible statements available from the scientific community on a given topic. It is different than a Scientific Theory in the sense that it generally only addresses one aspect of human knowledge while a theory attempts to craft an over-arching framework. Nevertheless, while different, a Scientific Theory is supported by a Scientific Consensus or possibly multiple consensuses. It is also important to note that while not infallible, it is the best choice available to us as any competing knowledge system would find itself inferior. Moreover, it is absolutely NOT an opinion, survey, or popularity contest among scientists. It is the best available option for knowledge credibility, which took countless hours of human endeavor to produce, and that deserves our utmost respect.

References

[3] National Center for Science Education. Definitions of Fact, Theory, and Law in Scientific Work.

[4] Wikipedia. Fact.

[6] The American Association for the Advancement of Science. Mission and History.